The white crosses and stars in Normandy’s American Cemetery seem to go on for miles. Buried under each, an American soldier who died fighting in World War II’s D-day landings and their aftermath. Each a life lost right in its prime, and all in just a few weeks.

Some markers have tiny American flags or handfuls of flowers nearby – reminders that all these men were individuals, with families, loved ones, and associated hopes and dreams. So many lives made hollow.

Truncated trees, representing lives cut short, add to the poignancy. Omaha beach, clearly visible below, does too. Families picnic on the sand, horses and their riders gallop across it – just a lucky break in time separating them from a very different, bloody Omaha seventy-five years ago.

It’s a place where you can’t help but reflect on life, death and think ‘lest we forget’. But it also got me thinking about courage. Where does it come from and what do we know about it? How did these men proceed up the beach, shells exploding all around them, without their legs turning to jelly? How did they and their compatriots manage to push on through all the gruesomeness, and eventually save Europe?

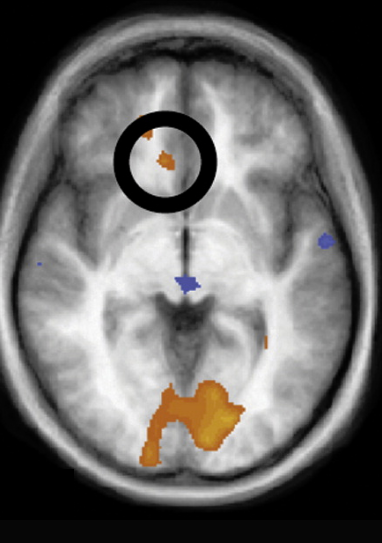

Courage is acting in spite of fear, and research has shown that a particular region of the brain is activated when people do this. The region is a tongue-twister called the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC).

The main study that showed this involved snakes, teddy bears and a conveyer belt. Either a live snake or a teddy bear was placed on a conveyer belt, and subjects could bring the bear or snake closer to them by pressing a button, whilst having their brain imaged through an MRI scanner. Those with a declared fear of snakes showed activity in their sgACC region (encircled below) when they courageously brought the snake closer to them.

When the subjects succumbed to their fear and moved the snake away, activity in this region dipped. Similarly, accustomed snake-handlers or those interacting with a teddy bear showed no such sgACC activity. When active, the sgACC region seems to counter the effects of chemicals responsible for fear, released from another part of the brain.

The sgACC region was clearly firing actively as the men ran up the beaches on D-Day. But what makes some people more courageous, and even more so in particular situations?

(Source: Caen Memorial Museum)

You may have heard of oxytocin, the cuddle hormone that plays a role in social bonding and love. Research has shown that oxytocin is released by the brain when various animal mothers face dangers to their children, and this also acts as a fear override.

Oxytocin isn’t exclusive to women; men release it too with the same effects, and the military are known to become second families to each other. Oxytocin enables a person to ignore fear and act to protect those they love, to race through enemy lines to pick up a wounded friend or secure enemy cannon. In the words of Richard Avramenko, “courage reveals what we care about…it reveals that which inspires us to overcome ourselves…what matters most fundamentally to the courageous actor.”

The extensive training that the solders went through was an additional bonus. Repeated training on how to deal with particularly stressful situations allows a person to act on autopilot when actually faced with these. Less brain activity is required to cope and energy can therefore be channeled into other things, such as dodging bullets or finding cover.

It’s easy to understand the science, but far less so to imagine being in the soldiers’ shoes on 6th June 1944. Some survivors say it’s indescribable and you just had to be there, but in the words of one soldier who fought at Omaha, “ you hear a lot about how long it takes to make battle hardened soldiers out of green troops. Listen, I got to be a veteran in one day, that day.”

Europe owes them all a humongous debt, as it does to the many other soldiers of different nationalities buried in cemeteries all around the world. Lest we forget.

Top tips for visiting Normandy’s American Cemetery:

- Normandy’s American Cemetery is easily accessible, and best combined with other D-Day sites to absorb what happened in Normandy during World War II. I visited a number of D-Day landing beaches, Pointe du Hoc, the Caen Memorial Museum and Sainte-Mère-Église (all mapped below).

- I split this route over two days, sleeping at two different hotels here and here, both of which I can recommend. Other hotels in the area are mapped below.